There were always too many kids like me. Least ways, I think so. Some were left on curbs or under the garbage in filthy alleys; a few ran away from home, but I’m not sure you can really call where they came from “home”. I’m just one of many. We’ve got flyers and satyrians and humans and all the rest, and we’ve got our peasants and our nobles, just like them other folks do, and we don’t fight nearly so much or so often—not with each other, anyway. The constable? Yeah, well, he’s another story.

I can’t remember how I wound up on the streets. None of the other kids could tell me, either. Sometimes I’d make up stories to myself to help pass the time on nights when sleep wouldn’t come. I’d dream—or maybe wish—that as a baby, I’d fallen out of a carriage or some such thing, and that my family had been looking for me ever since.

The story always ended with some finely dressed and faceless man and woman finding me, and not just taking me back in, but taking in all the other street rats, too.

But of course, that wasn’t the way it was; nor the way it’d ever be. I knew that. The other kids were my family—sort of. Jake was the leader, and he taught us younger ones how to steal bread or meat or cheese—and sometimes, if we were really lucky, even sweets! He showed us how to find safe places to sleep, and how to keep warm on winter nights when the wind and fog rolled in from the ocean, or cool on summer days when the sun made the cobbles hot enough to burn our bare and filthy feet. He told us how and when to be gentlemen—or warriors.

But out of all the other kids, the only one who really mattered, least ways to me, was Harmony. My eyes sting when I think of her, but I’m pretty good at keeping them dry. One … two … three blinks; it’s better—safer—if no one sees you cry.

The first time I saw her, she was hiding behind a big stack of crates that was going to be loaded onto a ship bound for Seven Skies or some such place that wasn’t here. She was crouched down behind them, hugging herself to stay warm and shivering like a leaf in the wind. She might as well have been naked for all the good the oversized blouse she was wearing like a dress was doing. It was cool but not yet cold down here by the water. It wouldn’t be long before Samhain would come, and the days were already getting shorter. She wouldn’t last a week without something warmer.

I thought she must be a street kid—probably a new one, judging by the flimsy thing she was wearing and the lost look on her face—and I made my way down the sand to where she stood by the pier. She never even heard me coming. She was shivering and rocking back and forth and watching the men as they slowly loaded the crates onto the big ship. And anyway, I can get around without being noticed. I’ve had a lot of practice. I’d have starved to death long ago if I wasn’t good at it. And believe me, I’m good at it.

I snuck up right behind her and tapped her on the shoulder. She jerked away and opened her mouth to scream. I leapt toward her and put one arm around her shoulders and a hand over her mouth. The scream turned into a muffled sort of whimper that didn’t sound much different from the cry of a seagull, so that was all right.

“Shhh!” I told her. “I’m not going to hurt you.” Her eyes got real big, like those of kids in Katy’s stolen picture books after they’ve seen a monster under the bed, and she started to struggle.

“It’s okay! Really!” I whispered frantically. “I just want to help you.” I let her go, figuring she would either run or stay, but if she kept flailing like that, a misplaced kick was going to bring the whole lot of crates down on our heads.

I took a step back from her, bowed the way Jake had told us was the way boys should do with ladies, and tried to look as harmless as I could. That, by the way, is something I’m not as good at.

“My name’s Daniel,” I told her, keeping my voice low, and then I waited to see what she would say.

For a long time, she didn’t say—or do—anything at all. She just stared at me with those same blue eyes that, I noticed, were pretty big even when she wasn’t writhing in terror. Her hair was a deep rich brown, like the color of the man’s booth on market day who sells little cups of coffee, and there were a few feathers caught in her locks—red and green and blue. Her face, though, was very pale, with a spray of freckles across her cheeks and nose, and it made me wonder if she’d been outside much in her life. I stole a look down at her feet, and though they were bare like mine, they were not rough and calloused like mine. In fact, they were rather bloody. Yep, she had to be a new one, poor kid, and hardly more than skin and bone—not that I was much more than that myself, but I’d nicked some fried potatoes from a sailor’s bag when he’d been distracted and was therefore feeling generous.

“Are you a satyrian?” she blurted out suddenly.

I blinked at her.

“Of course I am,” I said a little indignantly, reaching up and tapping the horn on the right side of my head where it spiraled out over my ear. “Got these, don’t I?”

The words were hardly out of my mouth when I realized I had forgotten to keep my voice down. There was a shout from the other side of the crates, and two big sailor men came barreling around them, bellowing and brandishing thick heavy rods at us.

“Run!” I screamed, and without looking to see if she followed my advice, I took to my heels and sprinted off down the beach.

It wasn’t long before I realized the sailors weren’t following. All they’d really wanted to do was scare us off. I looked behind me, and saw the girl running after me, her bushy hair streaming out behind her and whipping this way and that in the ocean breeze.

I stopped and let her catch up.

“I’m sorry,” she gasped when she reached me, clutching at a stitch in her side. “I’m so sorry.”

I frowned down at her. “Sorry for what? I was the one who forgot to be quiet.”

“I didn’t mean to upset you. It’s just … I never saw a satyrian before.”

“Well, that’s funny,” I said, “because we ain’t exactly rare.”

She blushed, the color of her face changing from a frosty white to alarmingly red so fast that it looked like someone was burning the flesh right off her skull with an invisible poker. Now that I thought of it, that’d make a great story to tell the other kids, and I promised myself to remember to do so on some dark night before Samhain.

I went over to the girl.

“What’s your name?” I asked her, wanting to make her feel a little more at ease.

“Harmony,” she mumbled, but she wouldn’t look at me.

“Well, Harmony,” I said, “I’m not upset. Not even a little. Just surprised is all. You never met a satyrian before, and I never met someone who never met a satyrian before. So, now we’re even.”

I put an arm around her shoulders again, moving very slowly so as not to frighten her away, and I guided her gently down the sandy slope toward the water.

“The first thing we should do is wash the blood off your feet,” I told her. “Jake says seawater keeps wounds from festering. You don’t want your feet to swell up and turn black and fall off, do you?”

If it was possible, her eyes got even bigger—so big, actually, that I worried a little that they were going to fall out of her head and just hang there bouncing on her cheeks, the way I’d seen some animal’s do. That didn’t happen though, which was good, because her eyes were pretty things, and ought to have stayed right where they were.

We sat down on the wet sand, just above the tide, and let the waves roll in over our feet for a minute. It was cold, and the cuts on her feet stung and made her wince, but I made her wait until all the blood was gone.

“There,” I told her, helping her stand up again. “Now you’ll be all right.”

“Is that the ocean?” she asked tentatively, staring out over the waves. The sun was sinking down past the horizon, and it was making the sky go all pink and orange and red.

“What?” I asked, bemused. “Of course it’s the ocean. What else would it be?”

She turned red again and didn’t say anything. I hadn’t noticed the first time, but the shade of her blush went very nicely with the blue of her eyes. Come to think of it, the blue of her eyes matched the blue feather that still lay nestled in her hair, just over one temple.

“You haven’t seen the ocean before, either, have you?”

She shook her head slowly.

“But it’s very pretty,” she said, as if that made up for it.

“Nah,” I told her. “It’s just the ocean. You’re the pretty one.”

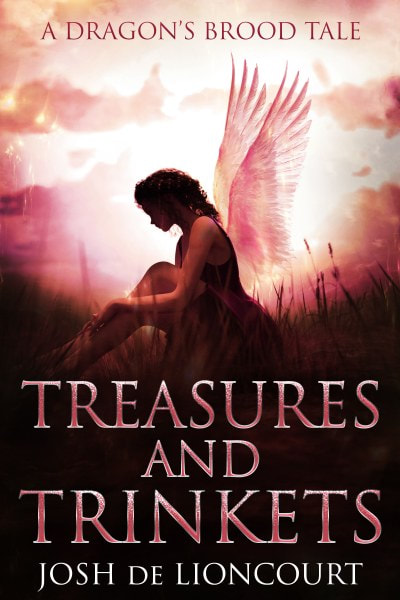

Treasures and Trinkets

A couple of days after the incident with the kid and the sweetcake, I was out there lying in the shade of one of the big pines, the voluminous skirts of my gown spread out around me like the carcass of a great punctured balloon. The pines were always the best ones to lie beneath, as the needles would pile up under their branches and make a soft place. Bright splashes of watercolors winked in and out of existence all around me as the sunlight filtered through the swaying branches high above. It was quiet, save for the tuneless babble of the stream and the music of a birdsong now and then.

On the ground before me were two dozen small carved pieces of wood, and another was in my hands. I was slowly whittling away at it with a knife I’d long ago spirited away from the dining table.

I’d been working on carving the chess set for a month or more by then, and I was nearly done. I had a vague notion of giving it to Lord Calom as a gift that winter solstice. Chess was one of the few things I knew he enjoyed besides his horses. He didn’t have much time for me. I wasn’t the son he’d wanted, and while I suppose he must’ve loved me, I didn’t see him often. I was just the girl that would one day inherit his title.

I set down the knight I was carving and looked down at the pieces I’d already finished. I had only a few pawns left to do, and then I’d need to figure out how best to stain half of them to be the black army.

There was a snap and a shriek from overhead. Startled, I looked up just in time to see a tiny form tumble out of the tree above my head and land in a heap hardly a hands-width from my knees. It was Lessa, the servant girl. She rolled over, untangling her limbs and scrambled to her feet, absently brushing the pine needles out of her hair, which seemed to burn as bright as the setting sun there in the shade of those great pines.

“Good day to you, mistress Madeline,” she said brightly, as if she hadn’t just trampled on the hem of my gown, leaving a smudge of dirt from the heels of her shoes. “I hear the sky is falling.”

I gaped at her for a moment, then let out a snort of reluctant laughter.

“What are you doing?” I asked. “Spying on me? Gossiping with the birds?”

Lessa seemed totally unabashed. “Now that you mention it,” she said, her eyes twinkling and her voice taking on that musical lilt that I would grow to know so well in the years to come, “there was a very nice sparrowhawk up there who was just getting to the good part of his story when you showed up and scared him off.”

I blinked at her, not sure if she was joking or not, but before I could say anything at all, she rushed on.

“Anyway, I was hoping to see you out here. My ma said that I should…apologize…” she made a face as if she tasted something sour, “…for speaking to you so the other day.”

I nodded gravely, as my governess had taught me to do when a servant displayed regret for something they’d gotten wrong. Acknowledge but don’t forgive, she’d taught me.

“Only that’s a lie,” Lessa went on, apparently unable to help herself. “I’m not sorry at all. That poor kid was starving! Did you see how thin he was? He was a skeleton wrapped in parchment…and you! You begrudged him the crumbs at your feet!”

She paused to catch her breath and glanced down for a moment, catching sight of my little armies of chessmen.

“What are those?” she asked.

My cheeks were burning, though whether that was from shame, embarrassment, or simple confusion, I couldn’t have told you. I felt a bit disoriented after that rush of words. I thought perhaps she’d insulted me, but I wasn’t quite sure how. Certainly she’d offered an apology, only to rescind it in the same breath, and my governess hadn’t ever told me how to act toward a mad person. So, instead, I let my gaze follow hers.

“They’re chessmen.”

“Oh, yes!” Lessa said, dropping to her knees—on the skirt of my gown again—and picking up the pieces one by one.

“A pawn,” she said holding it up. “And a knight…and a bishop…and a rook!”

“That’s a castle,” I told her.

“Of course it is,” she said agreeably. “‘Castle’ and ‘rook’ are just two names for the same thing.”

I frowned at her. “I thought a rook was a bird.”

She giggled, covering her mouth with her arm so she wouldn’t have to put the pieces down.

“Chessmen have had all sorts of names, you know. A long time ago these pieces were the infantry, cavalry, elephantry, and chariotry.”

It was my turn to giggle. Calling a bishop “elephantry” sounded kinda blasphemous to me—not that I’d ever put much store in any of the various gods the common folk worshipped.

“How do you know all that?” I asked her.

She shrugged. “Stories from my ma and her ma. They tell me stories. Like, did you know that once upon a time, a great wizard from the land of rug-making went to the land of the wise writers and brought a chess set with him? He challenged the king to a game, and if the king won, the rug-makers would tithe beautiful rugs to the king every year forevermore. But if the wizard won, the king would have to tithe great sums of gold to the wizard and the rug-making country instead.”

She stopped, holding up the knight I’d carved and watching the way a sliver of sunlight seemed to make the smooth wood glow.

“It’s very pretty,” she said a little breathlessly.

“But,” I said, my mind still on the story she’d started, “what happened with the game?”

Lessa looked at me, her head cocked to one side again. “Don’t you know?”

“If I did, I wouldn’t be asking.”

“Fair enough. Well, the king had one of his men sneak into the wizard’s room the night before the match and steal a great scroll that had all the moves he planned to use writ upon it. Marvelous tricks to crush an enemy in fewer moves than there are fingers on one hand!” She held up her tiny palm toward me, fingers splayed, to emphasize the point.

“The king stayed up all night long, reading the scroll and memorizing it, and when the next morning came, he won the match.” She set the pieces carefully back down with the others and dusted off her hands.

“And then what?” I prompted.

“And then the wizard was so furious he cursed the king and all his subjects so that their writing would look like nothing more than chicken scratch to the rest of the world forevermore.”

I sniggered again. “That’s a pretty good story,” I told her.

“I know,” she said. “But anyway, Ma will want me to help with the washing, and I’m already later than I ought to be. But I’ll tell her I apologized to you, and she won’t mind so much. Good evening, mistress Madeline.” She got to her feet again and started away.

I could’ve pointed out that, indeed, she hadn’t apologized—or at least, not one that had stuck—but instead I reached out and tugged at her sleeve, pulling her up short. Her eyes met mine warily.

I snatched up one of the knights I’d carved and pressed it into her hand. I’m not sure why exactly. It was just that it’d been so long since I’d had anyone who had talked to me—talked to me like a person and not a princess—that I wanted to give something back in return.

“Take this,” I said, and I forced her fingers closed around it. “And it’s Maddy. You can call me Maddy.”

For a long moment, Lessa stared at me with her head cocked again, and I got the sense she was sizing me up—trying to decide if I was serious or not. At last, she nodded solemnly, but I caught the glint of mischief in her eye.

“Very well then, mistress Maddy.” She spun on her heel and darted away between the trees, disappearing like a shadow.

“No, I meant just Maddy!” I called after her. Her tinkling laugh was the only response.

Comments

Post a Comment