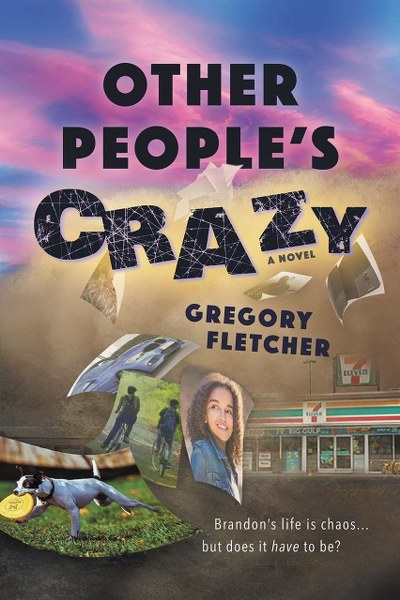

EXCERPTS from Other People’s Crazy by

Gregory Fletcher

1) From the top of Chapter Three: (468

words)

The problem with Lucky Charms was that

nowhere on the cereal box did it list how much you had to eat to actually

become lucky. It only described one serving as three-quarters of a cup,

but—what a joke—I always ate four times that amount. Shouldn’t my luck have

quadrupled? Unless bad luck

counted too. The cereal box neglected to distinguish between them.

Dirty cereal bowl in sink—check; lunch

bag—check; charged phone in pocket—check. I was ready to head out into the

fresh desert air, which in the early mornings was borderline comfortable. I

followed the second-floor exterior walkway to the stairwell, but instead of

going down, went up to the roof.

Mom sat tall with flawless posture on a

purple mat, breathing deeply and muttering words that only made sense to her.

Her feet were pulled up onto her thighs, and her hands rested on her knees,

palms up. There was a second mat beside her, but whose? Probably an equally

crazy neighbor who’d already left.

Huffing and puffing from the climb, I

took in the open-sky view of Mesa and the surrounding mountains. Within an hour

or so, it’d be too hot to stand out in the sun. Not until bedtime would the

rooftop be bearable again, but by then the view would be gone, leaving a

star-filled sky and the silhouette of the Superstition mountains.

Mom greeted me with her daily forecast.

Not the weather, which was always the same: sunny and freaking hot. Her

report had nothing to do with the weather. “Our morning will be filled with

honesty, compassion, apologies, and new beginnings. We will stand strong and

confident with truth on our side. At work, my day will be filled with

appointments, satisfied customers, and super generous tips.” She ended with,

“And yours?”

I never knew how to answer. Was I a

freaking fortuneteller? And why should I expect anything else but my usual

worthless day?

She finally gave in on getting an

answer, rolled up both mats, and headed down the flight of stairs. In the

apartment, she’d grab her bag, adjust the thermostat to 85 degrees, and lock

the door. I continued down the stairwell without her, at my own pace. Before I

reached the bottom, she passed me and cheerfully announced, “Beat ya!”

“I wasn’t racing.” A guy my size had no

business rushing down the stairs. Or running in general.

“Gets my blood moving,” she said.

“Feeling energized. Ready for a new day.”

I hadn’t felt ready for a new day in a long while, and I

doubted whether it had anything to do with how quickly I traveled from one

floor to the next. Maybe I took after my father in that department. Should I

ask her? I’d love to hear her response.

2) From Chapter Three: (456 words)

We walked to the old Ford Focus

parallel parked on the street. Mom pressed autodial on her cell. “Good morning,

Yoshi. Just checking you’re up and opening for me this morning?”

Yoshi was her cowboy friend at work who

dressed in flashy western gear and called me “pardner.” But he wasn’t really a

cowboy; he cut women’s hair and did highlights.

“Well, that depends,” she continued. “I

say this meeting will be reasonable, fair, and quick as a roadrunner.” … “You

betcha, right back at ya. Thanks. See ya soon.”

She disconnected and tossed me the car

keys. I stepped in the passenger side, and placed it in the ignition. She

remained standing at my side as if I were going to scoot behind the wheel. When

I didn’t, she walked around to the driver’s side. I closed my door, clicked my

seatbelt, and looked around to see what was taking so long. Now she was

standing at the driver’s door, waiting.

I reached over and unlocked it. “Why

didn’t you say something?”

She slid in. “I knew you’d figure it

out, sooner or later.”

“You could’ve knocked.”

“And you could’ve driven. Don’t you

want the practice? Isn’t that what a learner’s permit is for?” She waited, but

I clammed up. “Well?”

“If you want me to drive, just say so.”

She started the car, which sputtered

and stalled like always. She checked her three mirrors and then pressed the gas

pedal one time. “Sooner or later,” she said, but I wasn’t convinced she was

talking about the car. Sometimes, I just assumed we spoke two different

languages.

I turned on the A/C, and we were off.

“This is going to be a great day,” she

said.

Is it? I

thought. Because it felt like a crummy start as usual.

“Don’t you agree?”

“Seriously, Mom, how in the world is

this gonna be a great day? Look where we’re headed. I’m sure Principal

Arrington doesn’t want to see me any more than I want to see him.”

She seemed unfazed by my reaction. One

of us was out of touch with reality, and I was pretty sure it wasn’t me.

I looked her way again, and she bounced

her eyebrows. I felt sorry for my mother. She was gonna see a video that made

it look like her son was bullying, pushing, shoving, hitting, pinching,

kicking, and spitting. I had to warn her. “Trust me, it’s not going to be a

great day.”

“Don’t put those bad vibes out there.

They’ll come back to us both. Is that what you want?”

I had no idea what she was talking

about. “Since when is it up to me?”

Mom shook her head and muttered. “Sooner

or later.”

3) From Chapter Three: (429 words)

At a stop sign, Mom waited for a young

mother in the crosswalk, pushing her little boy in a stroller. He held a green

ball bigger than his head. As if determined not to drop it, he held it tight.

In the middle of the crosswalk, though, the ball shot up from his hands and

bounced back toward the curb where they’d started.

“You used to do the same thing,” Mom

said. “Hold something so tight, it’d pop right out of your little hands.”

Little

hands? I was amazed there was ever a time when a part of me was

considered little.

The mother returned to the curb and

handed the ball back to her kid, whose tears stopped immediately. She mouthed thank you and waved for us to go, but

Mom gestured for her to cross instead. This time, the kid kept hold of the ball

the entire way. He looked so proud of himself. I couldn’t remember the last

time I’d felt like that. I’m sure his mother expected him to remain happy,

innocent, and playful for the rest of his life. But what if he grew up to be

the biggest kid in his class? What if he was accused of being a bully? What if

he was actually being bullied by the smallest kid in his class, and so

humiliated he just took the punishment coming his way?

“Sorry.”

Mom looked at me. “For what?”

Had I apologized aloud? “Uh…just....” I

shrugged. If I could be so easily convinced I was a bully, it would be the same

for Principal Arrington. There was no stopping this video.

“Sorry for what?” Mom repeated.

“I’m going to be suspended for a few

days. You can drop me back home and still get to work in time.”

A car horn honked from behind us. Mom

gave the Ford too much gas. It lurched, then stalled out. She started it again,

and we were finally on our way.

She said, “No one’s asking you to take

a plea bargain.”

I had no idea what she meant—big

surprise.

“Brandon, did you hear me?”

“Speak English.”

“A lot of innocent people are tricked

into admitting guilt in exchange for a lighter sentence. If you do that, you’ll

be presumed guilty.”

“I’m already presumed guilty. There’s a

brilliantly edited video to prove it.”

“Honey, you’re the gentlest person I

know.”

“I’m not. I hate that kid; I’d do all

those things I’m accused of and more.”

“But I bet you didn’t start it.”

Neither of us said a word after that.

4) From Chapter One: (272 words)

“Hey!” a voice yelled from somewhere.

I looked up across the practice field,

but the heat was so thick the figure standing there wavered like a mirage.

Crouched, poised to take off, the hunching image looked to be a kid from the

nearby elementary school.

I responded, “Hey, yourself.”

The person shouted back aggressively,

“Don’t melt. Grease fires are a bitch!”

Was some snotty little kid making a fat

joke at my expense? Little did he know I had survived my entire middle school

years being called Sumo—as in the super fat Japanese wrestlers, wearing the

extra-large diapers. Thankfully, by the time I reached high school, I’d grown

to tower over my classmates, and the nickname magically disappeared.

Not wanting to pursue the conversation

but, then again, stunned to actually be acknowledged, I watched this small

person take off straight for me. The kid was focused intently, like in a highly

competitive game of Red Rover, where solo players bust through linked arms.

Only there was just me.

The bouncing blond hair and menacing

eyes became recognizable as my jeerer reached centerfield. Stuart, from my

English class, the smallest sophomore—and that was including the girls. No,

make that the smallest in the entire school, including the freshmen. He and I

hadn’t said two words to each other in the month since school had started. Now,

all of a sudden, he was running at me, elbows jetting back and forth, fingers

spread, aiming for me like I was wearing a bullseye on my belly. I waved for

him to stop. But it seemed there was no stopping this hazardous human missile.

5) From Chapter One: (308 words)

Never before had I been so happy to

hear the bell ring, bringing lunch period to a close. I walked to English

dreading the thought of Stuart continuing his scene in class.

The moment I walked in, Ms.

Lodewick beckoned me over. Without a word, she filled out a slip and handed it

to me. A hall pass, to see the nurse.

I was confused. “For me?”

“You’re bleeding,” she said,

indicating my neck and cheek. Making what I supposed was her best assessment,

she added, “Taking shade under a prickly pear pad?”

“Something like that,” I said.

“Best to stay indoors in this

heat.”

I couldn’t have agreed more.

“Go on,” she said. “The nurse will

fix you up.”

I walked out, pleased that a visit

to the clinic would delay having to see Stuart. By the time I was back, class

would be in full swing, and his crazy would’ve surely cooled off in the A/C.

When I rounded the corner to the

main hallway, though, he was headed my way. Get this: the smallest kid in the

school made me freeze with panic. He looked dusty, but there were no signs of

scratches or blood, nor any indication of trauma. Not at all like the PTSD I

was feeling. He was chatting it up with Saleh, another classmate, and strolled

by like nothing had happened between us.

At the main entrance, just before

the principal’s office and clinic, I veered off and walked out the front door.

As I leaned into the wall of heat, the dry air stung my cuts and scratches like

needles. I thought of going back inside so the nurse could tend to my wounds,

but what would I tell her? The littlest kid in the school had assaulted me? I

couldn’t explain it to myself, much less to an adult.

6) From Chapter Two: (883 words)

“You need to wake up. It’s gone viral.

You’ll have a lot of explaining to do.” Click.

Confusion. Because, on the one hand, I was

holding the receiver of an unconnected landline to my ear and hearing the voice

of a guy I’d never met. On the other hand, I knew exactly which video he was

referring to. When Stuart passed me in the hallway yesterday, he’d been

chatting it up with Saleh, who was always making short videos with his iPhone.

Was yesterday’s lunchtime assault his latest project? I threw the receiver to

the floor. The phone had been disconnected since Mom purchased our refurbished

iPhones. How it ended up underneath my bed was beyond me.

Also beyond me was why Stuart and Saleh

would’ve manipulated me into appearing in one of their videos. Why not just ask

me to play along? Unlike Stuart, Saleh didn’t seem to have a mean bone in his

body, so why the deception? And why me?

In my fifteen years of life, I’d never been

in trouble, but a month into my sophomore year, somehow, I was being morphed

into something new. Hit me, kick me—these

had been Stuart’s acting directions to get what he wanted. Even without my

really participating, there was enough footage to make him look like a victim.

With selective editing, they could portray me as the one who started the whole

thing—bullying the smallest kid in the school.

My cell phone rang. It had been so long

since it rang, I’d forgotten about the Constellation ringtone I liked so much.

As I reached over to unplug the charger, I slid off the bed, hitting the floor

like a beached whale. The scattered dirty clothes did nothing to soften my

landing. At least I was awake and out

of bed.

The phone stopped ringing.

“The bathroom’s yours,” Mom said from

outside my door. “That was me on the phone. You up? You didn’t answer the first

time.”

“Yeah.” I waited to hear the front door

close shut. She’d already showered, dressed, eaten, and was headed to the roof

to sit cross-legged, poised on her meditation mat, worshipping the morning sun.

I pushed up to my knees, and one leg cramped with a Charlie-horse spasm.

Painfully, I flexed my foot to extend the muscle and dug my thumb into the

knot. If I moved too quickly, the spasm would return. Sprawled across my

bedroom floor, I waited.

When I finally made it upright, I stopped

in front of the full-length wall mirror. The top frame now cut across my chin,

beheading my reflection. Seriously! Would I never stop growing?

I grabbed the frame of the mirror, lifted

it off the wall, pulled out the picture hook, and moved it up four inches. I

was able to push the nail back into the wall and re-hang the mirror without a

hammer.

Yep, my sneer was as pronounced as ever. I

sneered at my sneer.

Turning from my hideous reflection, I

grabbed the bottom of my T-shirt and lifted it over my head. It tore off in

shreds. My clothes all ended up either outgrown or disintegrated. Kicking my

way through the dirty clothes, I grabbed a clean t-shirt from my closet—a

triple large retro of some band from the 1970s. I threw it on and stepped into

a baggy pair of drawstring khakis.

I looked again at my sorry excuse of a

reflection. You big blob! Sumo! Human

punching bag! I made a fist to slam into the mirror, but stopped myself.

Mom would have a fit and refuse to replace it. Besides, I didn’t need any more

bad luck.

I pushed aside the hair hanging over my

eyes and scented my own B.O. I sighed, and got a whiff of my morning breath. I

stunk inside and out. As much as I wanted to get back in bed and tell Mom I was

sick, I knew she would feel my forehead and pronounce: no temperature.

Maybe I should just tell her about Stuart’s

film: I did it; video doesn’t lie. Might

as well admit it, because everyone would be convinced of one thing: I was a

monster.

Mom, with her jaw dropped and her eyes

wide, will shake her head in disbelief and start babbling crazy talk about my

aura or the need to turn my bed to face a different direction. I’ll point to

myself and give her a look, like Isn’t it

obvious who I am?

No, wait. The call on the unconnected

landline proved it was just a dream. So…good news, perhaps.

As I headed toward the kitchen for

breakfast, my phone’s text alert chimed. It was from Mom: Just heard from school. We’ve got a meeting

with the principal first thing this morning. Something about a video.

I should’ve

known any brief moment of optimism would be a fleeting one-off. Because my life

only attracts bad news. And the truth of the matter is: if it happened again,

Stuart running at me from across the practice football field, I’d still do all

those things his video showed me doing. And more. Because who else was I but

that person? So, if Stuart wanted a monster—a cold-hearted bully—fine. I just

might make his day.

When did you first know you

were a writer?

My great aunt and uncle, Matilde and Theodore Ferro, were writers

for classic radio, TV, as well as for various fiction, etc. They wrote the long

running radio serial “Lorenzo Jones and His Wife Belle” throughout the 1930s

and 40s. They wrote teleplays for live television, and, later, many classics

like “Leave it to Beaver,” “Peyton Place,” “The Patty Duke Show,” and dozens

more. When I met them as a young kid, we instantly connected. During a visit in

high school, they gave me a copy of one of their scripts from “Leave It To

Beaver.” On the plane ride home, I discovered it was missing the last couple

pages. I decided to write how I thought the script should’ve ended, and mailed

it to them. They telephoned with delight, “You’re a writer!” I moved to LA for

college, to be close to them, and we read each other’s work as if we were

peers. I will always be indebted to their support and all that they taught me.

What are some of your pet peeves?

Just a few:

·

racism,

·

sexism,

·

homophobia,

·

xenophobia,

·

a lack of compassion,

·

disinformation,

·

undervaluing investigative journalism,

·

relying on Facebook and friends’ opinions for

the news,

·

dishonesty,

·

narrow-mindedness,

·

bigotry,

·

prejudice,

·

bullies,

·

inhospitality,

·

failing to treat others like you’d want to be

treated,

·

undervaluing the arts,

·

not finding the time to read,

·

the inability to put the phone away during

social times with family and friends,

·

mindless violence,

·

religious fanatics who’ve lost the meaning of

religion.

Where were you born/grew up at?

My dad lived in New York City, and my mom in Long Island. When

they were married, they decided to move to Dallas, Texas, where I was born and

raised. Lucky for me, they brought along their theatre-going habits, which

quickly became my favorite childhood activity. I even studied children’s

theater at the Dallas Theatre Center, and acted in two of their mainstage

productions. The Dallas school district also supported the arts. Every year, my

school went to the Dallas Opera, Dallas Symphony, and Music Hall for musical

theater. If that wasn’t enough, my parents supported the idea of producing

neighborhood theatre in our own living room. (Clearly, I was heavily influenced

by “The Little Rascals.”) We must’ve produced four separate productions prior

to my high school years; at which time, my amazing drama teacher, Brenda

Prothro, directed us in two to three plays a year, and produced my first

full-length play in my senior year. What an amazing time and upbringing.

What inspired you to write this book?

I was having lunch with a friend who I

hadn’t seen in a long time. Within the first 15 minutes, she got a text and

abruptly had to go. I was like WTH! But when she explained that her son was

being bullied in high school, and she was being summoned by the principal, of

course my heart went out to both of them. As she was leaving, she said, “Of

course the odd thing is—my son is the biggest in his sophomore class. And he’s

being bullied by the smallest!” Without knowing anything else about her son,

bully, or school, my mind started trying to figure out how this began, and how

it would end. And Other People’s Crazy began its first trimester.

What can we expect from you in the future?

I’m halfway through Other People’s

Drama, which is book two, following Other People’s Crazy. The second

book centers on Brandon in his junior year of high school. And I suspect there

will be a third book in the series, with Brandon in his senior year.

I’ve also completed two new YA

manuscripts, currently looking for publishing homes:

Class of Numbers takes place in

a charter high school in New York City. A sub shows up to teach a class when a

sub was never called. The students’ names are substituted for numbers that

remain the same for the entire class. Then immediately afterwards, the sub

disappears. Who was this sub, and what do the numbers mean? The students are

determined to find out.

Tom and Huck—Sitting in a Tree re-images

Tom and Huck as gay 16-year olds, living in 1850 Missouri. Looking for love,

searching to belong, the adventures are told in the comedic spirit of Mark

Twain.

Advice you would give new authors?

Try your hand at other genres. Being forced to think outside of your

comfort zone can be rewarding, beneficial, and full of teaching moments. I

started as a playwright, but when I was encouraged to write fiction, I found

that I loved storytelling in this new genre, especially YA (young adult). And

because of my background in playwriting, I had a strong advantage with

dialogue, structure, and forward development.

Try writing a ten-page play, either original or based on some of

your existing work. My craft book, Shorts and Briefs, a collection of

short plays and brief principles of playwriting, will give you clear, concise

instructions, as well as examples. The principles of playwriting apply to all

creative writing, so expect some Aha moments when examining them from a new

angle. Plus, playwriting, like screenwriting, involves a community of artists,

so then writing won’t be so isolating.

Describe your writing style.

I like relating and feeling a human beating heart on the page. I

also like the contrast between darkness and white light. One without the other

becomes too off balanced for me. I love comedy when it’s balanced with drama.

And when it comes out of action vs. jokes. Whether contemporary or historic, I

like to see characters make choices, and the forward development that follows.

By the time I get to the final page, I want to have experienced and felt the

journey of the protagonist.

How important is reading?

So much good comes from reading. Yes, read as much as you can.

Limit TV and social media, schedule time to read-read-read. Different genres,

subjects, and authors—it will be enlightening, beneficial, entertaining, and

full of teaching moments. Along with reading, also write as much as you can.

The more you write, the more you’ll discover your strengths and what works best

for you. As with any craft, the more you practice, the more you mature and

excel.

Do you believe in writer’s block?

For

me, writing is about listening. (Who or what we’re listening to may be up for

debate. I’m guessing, we’re all listening to the same source, calling it

whatever name makes us comfortable: God, love, the universe, ancestral spirits,

the dearly departed, or any other celestial or otherworldly vibes.)

When

we stop listening—unable to connect with inspiration—this is writer’s block.

None of us truly knows where creativity and connection come from. Clearly, it’s

a fragile state that no one should take for granted, misuse, or neglect.

Therefore, when you honor and respect the gift of listening, you may be able to

avoid being blocked.

Does

an athlete put on a uniform and rush to the field or court to play? Does a

musician put together an instrument and immediately begin to perform? Does a

dancer step into the proper shoes and costume and rush to the stage at

“Places?” Of course not. So why does a writer grab a pen or open a laptop and

expect the words to flow? We, too, must warm up and prepare to write.

Get

rid of distractions. Stretch the muscle groups to rid any tension. Deeply

breathe to calm the mind. Prepare and unclutter your space. Allow

yourself to listen. Allow inspiration to channel through your mind, heart, and

fingers. Let the principles you’ve learned as a craftsperson help guide and

shape your words.

If

you’re unable to hear, then ask questions aloud, and listen for the answers.

(This works well at bedtime, too, just prior to falling sleep.) Or take a walk

in the fresh air and sunshine. Meditate. Practice yoga. Pray. If you’re still

blocked, turn to art. All forms of art can allow for inspiration.

Do

whatever works best for you to rid yourself of tension, anxiety, and stress.

These are the culprits of writer’s block.

(If

interested, I offer more tips and principles for creative writing in my craft

book Shorts and Briefs, 2nd edition, by Gregory Fletcher. Thanks for

the support.)

Comments

Post a Comment