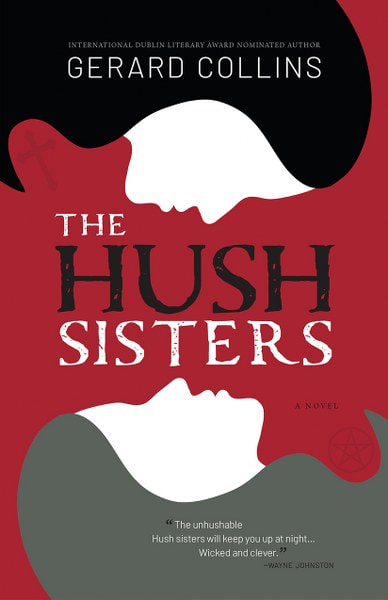

The

Hush Sisters

by

Gerard Collins

Genre:

Gothic Fiction

***49TH

SHELF UTTERLY FANTASTIC BOOK FOR FALL***

Sissy

and Ava Hush are estranged, middle-aged sisters with little in common

beyond their upbringing in a peculiar manor in downtown St. John’s.

With both parents now dead, the siblings must decide what to do with

the old house they’ve inherited. Despite their individual

loneliness, neither is willing to change or cede to the other’s

intentions. As the sisters discover the house’s dark secrets, the

spirits of the past awaken, and strange events envelop them. The Hush

sisters must either face these sinister forces together or be forever

ripped apart.

In The

Hush Sisters,

Gerard Collins weaves psychological suspense with elements of the

fantastic to craft a contemporary urban gothic that will keep readers

spellbound until the novel whispers its startling secrets.

Tell us about a favorite character from a book.

Little Women was the first novel I ever read, when I was only about eight years old, and so Jo March has always been one of my favourite characters – intelligent, witty, obstinate, loving, and a creative whirlwind. She writes ghost stories for which she is chastised, but eventually comes around to writing her story, much as I did with Finton Moon. I liked the title The Hush Women for my current novel in part because it was a subtle homage to Little Women, though I think the change to The Hush Sisters was the right one. Jo goes to New York on her own, which I did as well, though not to emulate Jo. That moment when she receives the galleys of her first book in the mail is etched in my brain, and I still feel weepy every time I see it because I relate to it, or, before I was published, wanted to relate to it, so much. Same with her relationship with her sisters. I had my older brothers, of course, and a younger sister, and we used to make up plays and put them on, record them, and all the rest, just as the March girls do. But I’ve always seemed to befriend women as I’ve gone through life, and I think, deep down, I was more of a Laurie who just wanted to belong in a family that celebrates art, life, and beauty instead of ignoring or just enduring these things. But Jo rebuffs his advances, which I admired because it would have been so much easier for her – and for her family – to just marry the rich boy next door. I admire her rebellious, creative spirit, I guess. I love her ability to forgive, as well, and to stubbornly obey her passion to write.

Louisa May Alcott based Jo’s story on her own life and family, of course, so, just a few years ago on a road trip, when I realized I was within driving distance of the Old Orchard House, I stopped in for a tour and was not disappointed. Looking out through that upstairs window that was Louisa’s and realizing that that was her view every day of her life while she lived there, it was one of my all-time favourite life moments. Naturally, I did some writing when I was there, and I’m so glad I did. Those kinds of moments are golden because there’s a connection you feel that’s more tangible in that moment than it could ever be when you go back home – a connection cemented by the written word.

What made you want to become an author and do you feel it was the right decision?

I became an author (as opposed to a writer) because I didn’t feel I had a choice. I already was a writer and always would have been even if I’d never published. In some ways, to me, a writer is simply a philosopher or observer of life who writes things down in order to figure them out. So, that’s what I do. The decision to keep going with it – insofar as it was a decision at all – was the right one, without doubt because, without writing, I’d be missing a major part of who I am. I could live without it, but I have no idea why I would choose to do so.

A day in the life of the author?

On a good day, I get out of bed, get a cup of coffee and go straight to my writing desk. But in the year of a new book release, or when I’m teaching university courses, it’s tough to make time every day for writing. But when I am writing, I tend to write in the morning, afternoon, and evening, even later at night sometimes. Everything else I do, I fit in between the writing sessions. Because I can write at any time of day (though I particularly like mornings), I find myself immersed in the book I’m writing even when I’m not sitting down at my desk or at a coffee shop. So, a typical day is spent either writing or thinking about writing, working out plot points or character traits, even if I’m taking out the garbage or going to the doctor’s office or grocery store.

Advice they would give new authors?

Don’t give up. The only writers who fail are the ones who give up. Hone your craft – study the stories of authors you admire. If you can, find yourself a good mentor who will be honest with you and who knows what they’re talking about. Take classes and workshops, but don’t let writing-related activity become the focus: only writing is writing. Also, as much as possible, make writing fun. Writing shouldn’t be all work and no play.

Describe your writing style.

Easy to read, precise, and filled with subtext.

What makes a good story?

For me, it starts and ends with good writing. Taut, precise prose by which you can tell the writer has studied her craft and knows what she’s doing with every word and piece of punctuation. Comma splice or inappropriate use of semi colons lose me every time because language, punctuation, and grammar are the writer’s stock in trade. It can’t be left up to having a crackerjack editor who’s done all the hard work before you came along. If you care enough to share what you wrote, you should care enough to learn the tools of the trade. Mistakes happen, and writers evolve. I get that, but there’s no excuse for not trying and learning.

Beyond that, assuming the writer knows how to write well, and their prose isn’t flowery or trying to impress, I look for a story that draws me in with a great – or at least very good – first line that promises an interesting story. The first line promises, and the last line seals the promise. In between, you just need interesting characters doing interesting things and having interesting, or challenging, things happen to them, but we should always wonder if it’s going to work out okay, from moment to moment. Every line, particularly dialogue, should have tension baked into it, and the best way to create tension is to make us care, and the best way to make us care is to provide details that bring the characters and situations to life, right from the get-go.

What are they currently reading?

I just finished When the Hill Came Down by New Brunswick author Susan White, which was very well done and Doctor Sleep by Stephen King, which I didn’t really enjoy, surprisingly. I’m now looking at 11-22-63 by King and am finding it quite good so far.

What is your writing process? For instance do you do an outline first? Do you do the chapters first?

I rarely work from an outline. When I think I’m ready – meaning I’ve carried the idea and characters around in my head for long enough, which usually means for years and years, if not just a few weeks – I just sit down one day and start to write. If what I’ve written feels potentially interesting enough, I’ll continue with the story, which sometimes can be a novel, but sometimes can end up being just a short story. Once in a while, I’ll even write a poem. Poems are more of the moment or the day, whereas short stories usually have their genesis in something I saw or experienced a while ago, whereas a novel is usually something I’ve lived with in my mind for a number of years while it incubates and waits for its turn.

At the beginning stages, I write and keep writing until I find that I need a bit more research before I can continue. Usually, at this stage, and at various stages throughout, I’ll interview my characters and/or ask myself a series of questions: Who is this character? Where is this going? What does this character represent? What happens next? And that sort of thing. I almost always find that in answering one or more of those questions, I begin writing again. So, for me, there’s usually no “writer’s block,” only moments when I recognize it’s time to stop and take stock, make sure I’m a bit more sure-footed as I traverse the next section(s).

For me, this is usually how it goes, over and over – writing and stopping, pausing, taking stock, asking questions – a number of times before I finally finish the first draft. I usually have a solid idea of the ending before I’ve written fifty pages or so. In the beginning, I’m just feeling my way around and sorting it all out in my head, on the screen or on paper. But I get more careful as I get fully into it, and I make more deliberate choices as I go. If I don’t know the ending by the time I’ve gotten about fifty pages into it, I force myself to give it serious thought and think of the best possibilities, and choose one. It’s best to write towards an ending you know than one you don’t know, even if that ending changes when it comes time to write it. It almost always does come out differently than I expected. But, then, I try not to have expectations for my characters, or my life.

What are common traps for aspiring writers?

The most common trap is to think that everyone cares what you’re writing. The second most common trap is to assume that no one cares what you’re writing. They’re about equal, really – between those who think they’re writing the most wonderful thing ever written and those who think their story isn’t worth telling. Both types are probably wrong, almost always. I also see a lot of writers seeking advice from people who don’t necessarily know but are keen on giving advice to anyone who will ask or pay for it. You need to develop a keen sense of whose advice is worth listening to.

Also, finish what you start. It’s the only way to know if it was worth writing at all. Submit your work, often. Listen to advice from professionals in the field – I’d suggest editors and other writers who have been traditionally published because they’re more likely to have been through all of this and had to deal with rejection and revision. Quite often, the quality of editing determines the quality of the writer. The more often you work with great editors, the more likely you’ll be a great writer, in time.

What is your writing Kryptonite?

If by “Kryptonite,” you mean the think that will make me stop writing or which I feel blocks me out and keeps me from moving forward in a story, I’d have to say nothing. I’ve overcome a lot – from rejection to life changes and medical emergencies and living with other people who have their own lives – and I’ve always kept writing. I no longer believe you need to write every day in order to write well, but you should take it seriously enough to do it at least half the days, depending on how much time you’re able to steal from other things in your life.

Social media is a trap, but a necessary one – more of an obligation than a responsibility. Video games are long gone from my life. The only thing that I find difficult is daily life that demands you run errands or spend time with people you don’t necessarily care to spend time with. I don’t do much of that anymore, but now and then, it happens. And even with the people I care about and want to spend time with, I have to set boundaries for myself so that I treat my writing self with the proper respect. In life, you’re expected to make time for a lot of different things; you just need to decide which ones are worth it to you, as well as how much writing means to you. Sometimes, the video game or banter with a friend are exactly what you need – but not every day and not for hours and hours every day. That said, I can get sucked into a weekend of The Crown, Penny Dreadful, or The Boys quite easily. But when that’s done, it’s time to work. The mind needs respite, just not every time you get a break from work. Some of those breaks need to be spent on writing, assuming writing actually means something to you.

Do you try more to be original or to deliver to readers what they want?

I don’t try too hard to be original. I figure the originality comes out in my voice or overall approach to something. If a character’s reaction seems trite or predictable, even boring, I’ll question that response and try to go deeper to understand where the character is really coming from. I don’t force things on my characters; I watch them and listen to them.

What I do try is to not let myself off easily. I try to write in a way that’s true to life, and life is rarely easy or convenient. If I write a scene, a gesture, or a bit of dialogue that – in rereading – seems to be written only to move the plot forward or out of a perceived need for things to be a certain way, or out of convenience, I’ll rethink it and rewrite, over and over, if necessary, until it rings true and comes from truth, no matter how dark or inconvenient. That way, I often write myself into corners which only the characters’ unique personality, propensities, and abilities can overcome.

If you could tell your younger writing self anything, what would it be?

Find a mentor or editor. Pay him/her if you need to. Also, polish those early manuscripts before starting another one. Make them as good as they can be, and send them out to every possible publisher until you’ve exhausted all possibilities. I’d hesitate to tell my younger self, “It’ll all be okay,” because that could mean any number of things, plus I doubt I would have believed myself. I still would’ve made all the same mistakes I’ve made, no matter who told me differently. That’s my own fatal flaw, I suppose.

What’s the most difficult thing about writing characters from the opposite sex?

“Difficult” doesn’t mean “impossible,” of course, and I think a man writing about women just needs to be aware that women and men don’t necessarily think the same or with the same set of priorities, and they’ve certainly spent a lifetime having a whole different set of experiences that are unique to being a woman. That’s a good starting point. I did the best I could – researched what I didn’t know and asked women some questions about things I couldn’t possibly know because I’d never had experience with those things, except as a man. Almost all the readers and editors I worked with were women, and there wasn’t much that they called me on, though there were some minor details to correct. I trusted in those readers quite a lot in writing The Hush Sisters, though I never pretended to know what it’s like to be a woman. The perspective is third person, rather than first. As always, the goal for me in writing is to try and understand, explain, or empathize with something or someone I didn’t previously fully understand – I do that for myself and not really for anyone else. I figure if I can write myself into a state of understanding, as well as I can, at least, then maybe I can write a believable story that also gains some empathy and understanding for the subject.

All that said, I’ve spent a lifetime listening to women, being best friends – or just friends or colleagues – with women, talking with them, observing, and enjoying the company of women because their language and proclivities, generally, are far broader, deeper, complex, and more interesting to me than those of the average male, at least from my experience

From the moment I started writing, I was compelled to write about women - I mean, you kind of have to. A literary world without women in it just wouldn’t be interesting to me except maybe as a literary experiment, just as a literary world without men wouldn’t be as interesting as the real world that includes all genders. I’ve written novel manuscripts that were, in the beginning about men, but I unconsciously found myself drawn more to the woman’s perspective. I’m not even sure why that is – I haven’t really tried to parse it out. I just know that women are far more interesting to me as a writer, but also as a listener of music, reader of literature, or viewer of movies and television shows. It doesn’t mean I know what it’s like to be a woman. I certainly don’t. But it does mean I have a pretty deep empathy and field of vision when it comes to women. It’s a start.

How long on average does it take you to write a book?

It depends on the book. Finton Moon took over a decade of writing and rewriting. Moonlight Sketches took about six years. The Hush Sisters was the better part of a decade, with most work done in the past year. Keep in mind that there’s a life in there too – getting a Ph.D. and teaching, writing a dissertation that took four years, and so much else. The next one coming out, The River in Winter took only six weeks to write and not much time to edit. I’ve completed another manuscript in which I gave myself a one-month deadline, which I met. Another time, I took a semester off from grad school, thanks to a federal grant, and wrote an entire novel. I take the time that life affords me, but I always create my own opportunities and meet my deadlines. But I would tell first-time novelists or writes in general: your book doesn’t have to take five years to complete. The object in the rearview mirror might be closer than it appears. On the other hand, as an industry person once told me, “It takes as long as it takes.”

Do you believe in writer’s block?

I think a person can talk themselves into almost anything. If you believe you’re blocked, then you probably are, and, quite often, it’s your own fear of being blocked that got you there.

Since getting a concussion about four years ago, I have a different take on writer’s block. For many months, I was simply unable to write. It wasn’t that I was blocked: it was physically excruciating to attempt to write and when I did try, even for a minute or two, it left me debilitated for several days at a time. It’s a different thing than humble writer’s block, I know, but it gave me some empathy – as someone who has always written and never had writer’s block of any kind before – for those who find themselves unable to write.

I still maintain that there’s a difference between “can’t write” and “have myself convinced I can’t write.” When it comes down to it, you can write yourself out of so-called writer’s block. Interview your characters, ask them questions, ask yourself questions, and always write out your answers in an engaged way. Write about something else, anything else that interests you, and come back to the piece that supposedly has you blocked. Even if it takes months or years. The main thing is to finish it.

But the key isn’t necessarily to force yourself, but to relax. Most creative pursuits go better if you relax, with just the right amount of intensity, or curiosity, about how it will all turn out. Relaxation aside, though, you do need to sit your butt in the chair, pen or fingers poised, and put in the time.

Just put in the time.

Excerpt from The Hush Sisters by Gerard Collins

Sissy fixed the tea—red mug for Ava and black one for Sissy—and brought it to the table where she took up her favourite seat in the entire house. From there, if she turned around, she had a view of the back garden and, in a natural sitting position, a perfect line of sight through the kitchen and down the hallway toward the curved staircase with its wide bottom step, past the exposed brick chimney opposite the stairs, and all the way to the red front door. “Sorry there’s no sugar or cream,” she said.

“Don’t tell me—you gave them up?” Ava flashed a cheeky grin.

Sissy smiled and said, “Months ago.”

“You’re practically a monk,” said Ava as she drummed her scarlet-painted fingernails on the tabletop. “I don’t know how you stand it here with all this...old stuff.”

While she sipped from her dark mug, Sissy considered her response and wished for the drumming to stop. “It’s comforting to have all these connections to the past.”

Ava’s red-lipsticked mouth appeared to form a question. But instead of speaking, she closed her eyes and tilted her head back. “Listen.” Ava paused, allowing the natural world to have its say—the crick-crack of the walls and floorboards whenever the wind gusted, the long, inquisitive trill of a robin redbreast in one of the trees, and the chitter of a squirrel. “It’s like discordant music.” She smiled.

“The old place has its charms,” Sissy said.

Ava composed herself, willing the humour from her business-blue eyes. “You know I couldn’t live here.”

“I’m not in favour of selling,” Sissy said as she fingered the handle of her mug. “I told you already.”

“But you can’t afford to keep it up. Not by yourself.” Ava sipped her tea. “I don’t know how you live in this old city.”

“Old, old, old,” said Sissy. “That’s all you ever say about things around here. The house is too old. The city’s too old. Our father was too old to keep living here—”

“I still think he would’ve been better off at the old folks’ home till the end.”

“We both would’ve been better off if he’d stayed there.” Sissy could feel herself hardening, on the verge of closing herself off and shutting down. “But I had nightmares about him, especially after Harry…anyway, now we’re deciding this together.”

“It’s an old house, Sissy. It’s too big for you. You told me yourself you can’t afford to run it, financially or otherwise.” Ava glanced past Sissy and toward the garden, out to where the bright yellow sunflower heads bobbed in agreement with the late-summer breeze. “It’s as much mine as yours. I have a say.”

“But I can’t see it as a bed and breakfast. People coming and going. No privacy. Always serving meals, making beds. It’s not how I want to spend the rest of my life.”

“Then come live with me.”

Sissy caught a glimpse of the barefooted ghost girl, leaning out over the curved part of the stairwell that overlooked the entrance to the living room, her hair draping the shoulders of her white dress. Her hands grasped the railing in front of her. Hello, Clair. She didn’t respond, but Sissy could tell Clair was listening by the way she became very still.

“You know how I feel about Toronto, Ava. You know.”

“Yes, well, you’re not the first girl from St. John’s to hate Toronto.”

“It’s cold there. And dark. And money-driven.”

“And it’s not St. John’s. You might as well admit it. You hate change. You always have, and now when there’s an opportunity—”

“Opportunity? I have a life too, Ava. Look around you. Our parents, love them or hate them, lived here. Their parents built this house, and now I live in it too. Harry and I shared a marriage here. We were married in the backyard.”

“And you’ll be buried in the backyard, too?” Ava shrugged. “It’s just a house. I mean, sure, it’s big and glorious in its own way. In spite of everything bad that happened here, we had some fun times. I get it. My God—the big dinners, the fancy cars in the driveway. The Craigmillars. The Monroes. They all came here, didn’t they?”

“I used to hide in my closet till they were gone.”

Clair turned her head slightly toward the kitchen.

“I know you did,” said Ava. “I assumed it was just too much for you.”

Clair suddenly sat down on the fifth step and started to rock, as she often did, a motion Sissy could vaguely detect.

“They all loved you. You were the cute one that sang and played ‘Silvery Moon’ on the Steinway.” Sissy nodded toward the living room where the Victorian grand piano, with its reddish-brown mahogany satin finish, sat facing the wall.

“It was expected.” A shadow crossed Ava’s face, which caused Sissy to study her older sister, the unexpected softness of her features, especially the crow’s feet. The blonde hair suited her, she supposed. “You could have played, too,” Ava continued. “You play beautifully.”

“I didn’t want to.”

“That was your choice.” Ava grinned. “‘Amazing Grace,’ I remember. You played lots of hymns and Irish music.”

Sissy shrugged. “I’m just not as comfortable with attention as you are. I played for myself.” She sauntered to the living room and stood beside the piano. “You have even more memories here than I do.”

“Mostly bad ones.” Ava turned and watched Sissy as she caressed the edge of the closed key cover of the piano.

Sissy lifted the cover, which made its usual soft thump, and peered into the keyboard. She jabbed at a black key, a sombre A-flat that travelled and lingered, till at last it fell to a whisper and then became silent.

“But we’ve barely even talked about the bad ones.” Ava followed Sissy into the living room as the note vanished. She sat down on the piano bench, as Sissy drifted away. “We’re a family of mutes,” said Ava.

Sissy closed her eyes, feeling as if she were leaving her body. When she turned and opened them, she found herself looking at the Rostotski portrait over the piano. “What’s done is done. Talking about it wouldn’t serve any purpose.”

Ava looked up at the same portrait. Through the upper corner of the living room window, sunshine streamed in and struck a mirror on the opposite wall above the fireplace, which reflected toward the piano and divided the photograph—the older sister awash in amber light, the younger one shrouded in darkness. The sisters thought of it as their own private Stonehenge, when the sun struck that mirror at the precise time of day, during a certain time of year, to light up the half the Rostotski.

“I remember when that was taken.” The conviction in Ava’s eyes intermingled with sadness. The waning sun shone on the left side of her face as well as that of her youthful likeness. For a moment, she seemed suspended in time, halfway between fact and fiction. Reality and dream. Present and past.

GERARD

COLLINS is a Newfoundland writer whose first novel,nbsp; Finton Moon

, was nominated for the International Dublin Literary Award and won

the Percy Janes First Novel Award. His short-story collection,nbsp;

Moonlight Sketches , won the NL Book Award, and his stories have been

published widely in journals and anthologies. He lives in southern

New Brunswick.

$15

Amazon giftcard,

ebooks

of Finton Moon and Moonlight Sketches by Gerard Collins

-

1 winner each

Comments

Post a Comment