Having

Children Chapter 1: Wedding Gift, p. 9 (469

words)

She’d

been in Italy a year before meeting Enzo, who intrigued her as soon as she saw

him because his look was more casual American than polished Italian. He was

working on an advanced degree and supported himself making leather goods.

Sylvie made him teach her how. Soon she was showing him how to streamline his

operation by making reusable patterns. In a matter of weeks they were spending

most of their time together. She luxuriated in his company when they were

together and longed for him when they weren’t. To her, their synergy and her

intense feelings spelled love.

She was

cutting a pattern and he was attaching a cowhide strap when he blurted out that

he wanted to have a family someday.

“You’re the

first man I’ve known who said he wanted children,” she replied.

Truly, she’d never discussed

children with a man. But last year in Mantua, she saw her 28-year-old friend

Patrizia panic about her waning fertility as her male friends said by age

twenty-three a woman was too old for marriage. Such pressure troubled Sylvie

too, although she wasn’t raised to be a woman who dreamed of motherhood but

rather one to finish college and have a career. In fact, her mom had never

exposed her to newborns, and children misbehaving in public always

prompted Mom to mutter, “Lousy

little kids.” Whenever Sylvie had asked Mom why she’d had children when they

clearly annoyed her, she replied, “Society expects it.”

Now

Sylvie told Enzo, “I’m not ready to have children,

if

I ever do.”…she wasn’t raised to be a woman who dreamed of motherhood but

rather one to finish

college

and have a career. In fact, her mom had never exposed her to newborns, and

children misbehaving in public always prompted Mom to mutter, “Lousy little

kids.” Whenever

Sylvie had

asked Mom why she’d had children when they clearly annoyed her, she replied,

“Society expects it.”

Now

Sylvie told Enzo, “I’m not ready to have children, if I ever do.”

“Ready?”

Enzo said. “Capitalist hogwash! Children enrich life—they are life! You just

need some extra food and clothes and you pack him up and bring him along. Think

what fun with a little baby playing around!” He pulled her close and gazed into

her eyes, reminding her

how long

she’d yearned to escape suburban artifice and plunge into life’s core, to feel

its pulse, to be more in her body. She’d experienced such exuberance in Italy

where parents included children in ways unthinkable in Sylvie’s suburban

American world. Children were often seen eating at restaurants late into the

evening, attending adult parties, listening in on their parents’ conversations,

so she was starting to see them as life-affirming rather than an obstacle to

her career plans. She enjoyed discovering these cultural differences with Enzo.

Stereotypes Chapter 2: Honeymoon, pp.

15-16 (606 words)

Enzo

took the wheel when he was up and drove all morning, saying he’d never seen

such empty spaces. When the map told them they were near the Wildrose

Reservation, he pulled over at the sight of a hitch-hiking man with long black

hair and a deadpan face who ambled to the car and climbed in, reeking of

alcohol. “I want to talk to Indians. The real Americans,” Enzo said.

The man

didn’t reply, but as they approached a crossroad with no signs, trees,

buildings or anything that distinguished it, the man gripped the doorknob and

said, “I’ll get out here.”

Enzo

pulled over. “Is this the reservation?” The man released the doorknob. “OK, you

keep going. You go talk to Strong Hawk. Very, very wise man.” Then he ducked

out of the car and walked backward, bobbing at them before turning down the

crossroad.

Enzo

said, “I heard Indians are alcoholics. I hope we find a sober one.”

“Do you

realize how many stereotypes you have? You also say the Indians are an

oppressed proletariat ready to rise up.”

Enzo

said, “That’s social science, not a personal stereotype.”

“Not

everyone is Italian, you know. Or even European.”

At an intersection where a small

sign indicated Wildrose Reservation, Enzo turned onto a two-lane road of bumpy,

cracked asphalt. Along both sides lay rusting cars, some with flat tires,

others at such odd angles Sylvie couldn’t figure how they’d ended up that way.

She’d been right in wanting to leave the States, she thought. This place proved

its violent nature, its enduring abasement of those most vulnerable.

Enzo

observed, “Don’t they have mechanics out here?”

“Please

stop it,” she said.

They

drove through barren snow-dusted plains dotted with naked trees until reaching

a row of angled parking spaces. Unpainted clapboard buildings—two tourist shops and the post office—comprised

the town. Enzo kept the engine running to stay warm while Sylvie entered

the larger store called, with

little imagination and a nod to tourists, “The Trading Post.” Tables were laden

with necklaces and bracelets of Venetian glass beads, an array of turkey

feathers dyed in gaudy colors, silver jewelry and Wildrose souvenir key chains

and ashtrays. She visited the

other store and found shelves of

books and spinning metal racks of postcards presided over by a white man in a

plaid shirt and bolo tie sitting on a stool behind a counter. She picked up two

postcards and a few books about Lakota history and took them to the counter.

Through the window she saw Enzo standing by the car smoking.

“That’s

a good book, but here’s some better ones.”

The

owner-proprietor-cashier walked her to the bookcases and pulled out one on the

Lakota and Cheyenne. Sylvie wondered how he was allowed to operate a store

on the reservation.

“Have

you heard of Strong Hawk?” she asked.

“Of

course,” he answered. “James Strong Hawk.”

“How can

I find him?”

“Funny,

that guy’s becoming famous. Stay on this road, go ‘round the first curve, cross

the bridge, then go about ten miles to another big curve. There’s a sign in

front of his house with his name on it.”

She

carried her purchases to the car. “Why didn’t you come inside?”

Enzo

shrugged. “Wanted a smoke.”

They

followed the directions until there at a curve where the road turned sharply

left stood two small houses, a modular house and another house pieced together

with found objects like an art installation—wooden crates, car windows, sheets

of corrugated metal, tree trunks holding up the roof, even a pair of antlers. A

sign between the houses read, “Strong Hawk’s Paradise.”

Old Wives Tales Chapter 4: Rules, p. 38 (495 words)

The next

morning, Sylvie went to return Olga’s milk pail. She breathed in the scent of

tilled earth arising from the hot fields as she walked along the cobblestones

that lay like rows of solid bubbles even after centuries of hooves and feet had

worked to flatten them. Coming through a dark passageway, she entered the

bright piazza and tripped on a cobblestone’s humped back and the pail flew from

her outstretched hands as she stumbled. Olga and Griselda were perched on a ledge,

the tiny vines of their calico aprons extending up from the stones. Relieved

she didn’t land on her belly, they heaved a loud sigh as from a single breast,

then laughed.

“We

always fell down, too,” said Griselda.

“When I

was pregnant, I fell down a whole flight of stairs,” said Olga.

“Maybe

by the time I’m used to all this weight, the baby will be born,” Sylvie said,

leaning sideways to pick up the pail.

“Yes,

and you’ll be carrying the little one in your arms instead,” said Olga.

Sylvie

was about to sit when Griselda gasped so loudly that Sylvie jumped up,

expecting to find a snake slithering behind her.

“No! You

might lose the baby if you sit on that cold stone!”

Sylvie’s heart pounded. “I could’ve

lost it from fright just now!” Olga folded up her sweater to make a cushion for

her.

“Just

beware of the extremes,” said Griselda. “Hot and cold.”

Sylvie

wanted to rebel against all these restrictions but, without facts to counter

them, didn’t dare. Besides, she admired Griselda and Olga. They’d never sit in

Café Miraggio and discuss whether the economy balanced on women’s backs. But

who in Café Miraggio could do what they did, bring forth life out of soil,

prune grapevines and tie their branches to trellises, gather wood into bundles

and sling them over their shoulders, scramble up the hill and out of sight on

spring days when porcini were growing in their secret places, move quick and

sure, like rabbits darting home? When Sylvie was eight, Mom handed her a seed

packet bearing pictures of bright blue morning glories, suggesting she plant

them by the arbor. Smiling, Mom said, “Read the instructions.” Sylvie took the

seeds outside, poked holes in the soil with her finger and dropped them in, not

knowing she’d planted them too deep, and quietly despaired when they never

surfaced. She never mentioned it and Mom forgot about it. And when she planted

seeds in the garden Olga gave her, she regarded the seedlings with awe, as if

she’d performed a miracle. But no, it’s the spirit of life pushing through the

earth as the spirit of life was in her belly. Where Mom struggled underneath

male definitions, these women, growing out of their village stone, knew how their

femaleness fit not just on the planet but in society. It was as if they

included her in their water line.

Consciousness Raising Chapter -- Real Women, p.118 (799

words)

Sylvie

had called the number in The Phoenix classified ad and a woman gave her the

address, so on Tuesday evening she hitchhiked there because it was faster than

the subway. After days of not seeing Saul, she managed to conjure only a hazy

image of him.

Lyn

answered the door wearing faded Levi’s and a men’s embroidered Guayabera shirt.

She led the way upstairs where women sat in a circle on metal folding chairs or

floor pillows. Sylvie nodded hello and sat beside Lyn who said, “Last time,

Jean, you were talking about the rape. I’m wondering how far you want to go

with this?”

“I don’t

know. But I don’t want my husband to find out. He’d never believe me.”

“Are

you kidding? If I told mine a story like that, he’d beat the crap out of me,”

said a woman married to a cop, flicking ashes into a blue jar lid.

“But

Jean,” Lyn continued, “besides your husband believing you seduced your rapist,

what about your feelings?”

Jean

paused then said, “I’m sorry, but I don’t want to talk about it now.”

Lyn

nodded. “What we as a group can do is give sisterhood, and that should be a

comfort. But we also have to keep raising our own consciousness and that of our

brothers. This is all about learning. Most women spend their time talking about

their clothes, hair, makeup and boyfriends. Wouldn’t that tend to make us feel

intellectually inferior? Aren’t the ads geared toward making us think we must

be attractive because our life job is to get a man? Why shouldn’t men spend all

their time becoming enticing? For that matter, why should anybody?”

Some

women shifted in their seats. “That’s easy for you to say in your ivory-tower

world, Lyn. But we’re out there with real men,” said the woman in make-up.

“Oh

yeah? What’s a real man?” said Lyn. “If we knew what men thought they should

be, we could support them. But if a man doesn’t know who he is, how can we help

him from remaining a child?”

“Are we

supposed to know?” said Make-up Woman.

A woman

who Sylvie figured to be about twenty-five spoke up. “Since you’ve mentioned

children . . . .”

They all

laughed.

“. . .

I’ve been losing my mind. I used to be an artist, but now I’m a mom.”

“That’s

an old theme,” Lyn said. “When you have family responsibilities, it’s tough to

reconcile that with your urge to make art.”

“Lyn,

this is one time I’m going to disagree with you. My mind is totally involved

when I make art. It’s not an urge.”

“Point

taken,” said Lyn.

A

braless woman with pendulous breasts beneath her peasant blouse said, “We let

men be assertive because we’re sorry for them. They can’t have babies. Creating

and developing human lives is the most important work of art anyone can do.”

“Barb,

I’m glad you said that,” said Lyn. “Women have always been subjugated because

they have the babies. Because of that role they don’t shine out in the history

books.”

Barb

continued, “But if we proved we could do the same as men, if not better, where

would that leave them?”

“Why

should I care?” said Artist Mom. stayed home and raised children while we were

out politicking or painting, they’d all become impotent. Or do you think we’d

eventually become aggressive enough?”

“That’s

absurd,” said Jean. “Women attacking and raping helpless men, like dirt

attacking a shovel to make a hole in it.”

“Listen

to yourselves, sisters! That’s a trap,” said Lyn. “It’s what Marx called

‘wearing your chains willingly.’ We are our own oppressors.”

The

murmuring stopped. Everyone gaped at Lyn inanticipation.

“I want

men to understand women and treat us fairly,” Sylvie said. “I remember when my

brother asked me—maybe I was thirteen—whether I thought of myself first as a

person or as a girl. And I said, as a person and he said he thought of himself

first as a boy.”

Lyn

said, “Because he recognized the power boys had.”

“I

mean,” Sylvie continued, “I always thought of myself as a human with a mind,

and then a body.”

“You’re

lucky if you didn’t internalize those messages that said otherwise,” said

Make-up Woman.

“Yeah,”

said Artist Mom, “like girls can’t roughhouse, play sports, get dirty, be loud

. . . .”

“I

always thought of boys as just so sad,” said Mrs. Cop.

“Me too!

They didn’t have friendships like we have.

They

always seemed so burdened,” said Barb.

“It’s

those cocks they have to carry around,” said Artist Mom. Laughter swept around

the circle.

Lyn

said, “Who here has a son?”

A few

hands went up.

“We have

a responsibility to raise our sons differently.”

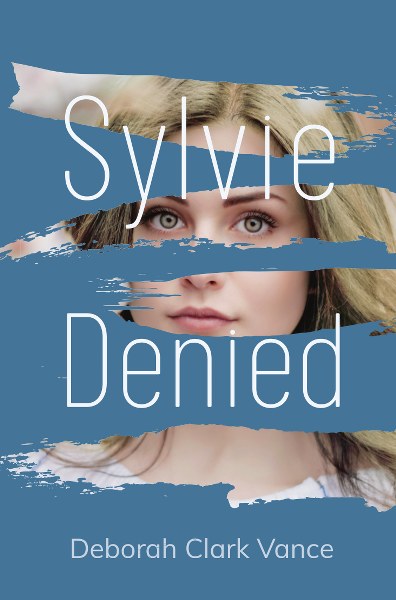

I'm honored that you included my book "Sylvie Denied" on your blog site. Thank you so much!

ReplyDelete