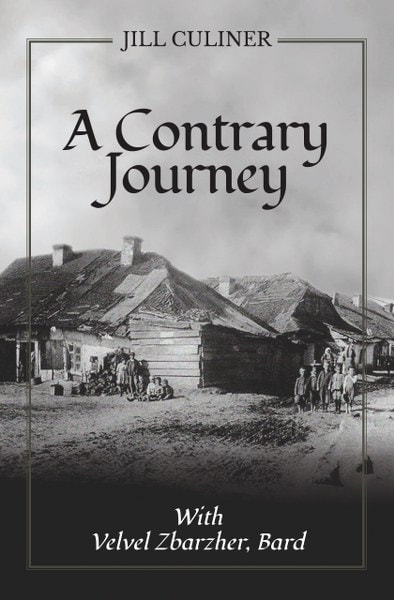

A Contrary Journey with Velvel Zbarzher, Bard a Nonfiction Biography by Jill Culiner ➱ Book Tour with Giveaway

A Contrary Journey

with Velvel Zbarzher, Bard

by Jill Culiner

Genre: Nonfiction Biography, History, Travel

Culiner's intrepid pursuit of the elusive troubadour and the lost world from which he emerged enriches us with a double depiction of the turbulent times and places of the bard's era and the galloping commercialization of our own. Like a chef who manages to document great recipes before they disappear, Culiner serves us an utterly delicious feast of flavours we do not want to lose.

Robin Roger, writer, reviewer, Associate Publisher, New Jewish Press 2016-18

Invited by Culiner to join her travels to find Velvel was a gift in isolated pandemic times. Part history, part biography and part literature, the writing poetically transfixed. Train rides, villages, and Velvel's life move between magical realism and extraordinary insights into Jewish history generally missing in heritage tourism.

Daniel J Walkowitz, Professor of History Emeritus, Professor of Social & Cultural Analysis Emeritus New York University, author of The Remembered and Forgotten Jewish World

A captivating romance, a thrilling mystery, a fascinating tour back and forward in time, and so much more. Culiner takes us out of the contemporary fast-paced, digital society and superbly redraws the varied contours of the shtetls of Eastern European countries of yore via one remarkable itinerant Jewish existence. The book brilliantly brings back to life the unjustly forgotten Hebrew poet and Yiddish melodrama author, Velvel Zbarzher, a significant precursor of Yiddish theatre that moved from Galicia to Romania, the Russian Pale of Settlement, Austria, and finally Turkey. A breathtaking read!

Dana Mihailescu, Associate Professor of American Studies, University of Bucharest

What a beautiful book! The writing is clear and direct, the subject matter is interesting and important, and the characters are lively and realistically portrayed. In short, it's a good piece of reporting, and was entirely successful in wafting me to another time and place.

Barrington James, former foreign correspondent for the Herald Tribune and UPI, author of The Musical World of Marie Antoinette

The Old Country, how did it smell? Sound? Was village life as cosy as popular myth would have us believe? Was there really a strong sense of community? Perhaps it was another place altogether.

In 19thc Eastern Europe, Jewish life was ruled by Hasidic rebbes or the traditional Misnagedim, and religious law dictated every aspect of daily life. Secular books were forbidden; independent thinkers were threatened with moral rebuke, magical retribution and expulsion. But the Maskilim, proponents of the Haskalah or Jewish Enlightenment, were determined to create a modern Jew, to found schools where children could learn science, geography, languages and history.

Velvel Zbarzher, rebel and glittering star of fusty inns, spent his life singing his poems to loyal audiences of poor workers and craftsmen, and his attacks condemning the religious stronghold resulted in banishment and itinerancy. By the time Velvel died in Constantinople in 1883, the Haskalah had triumphed and the modern Jew had been created. But modernisation and assimilation hadn't brought an end to anti-Semitism.

Armed with a useless nineteenth-century map, a lumpy second-hand coat, and an unhealthy dose of curiosity Jill Culiner trudged through the snow in former Galicia, the Russian Pale, and Romania searching for Velvel. But she was also on the lookout for a vanished way of life in Austria, Turkey and Canada.

This book, chronicling a forgotten part of Jewish history, follows the life of one extraordinary Jewish bard, and it is told with wry humour by award-winning Canadian writer Jill Culiner.

After the decline

of Polish power in the nineteenth century, towns degenerated. Foreign travellers sneered at the heavy sour rye

bread, the salt butter, the simple meals of eggs and fish, and at village wretchedness and low sanitary standards. But, this is a marshy country where folk were gnawed into misery

by all manner of winged and crawling beasties; where, in the rainy season,

horses sank to their bellies in mud and could only be pried out with heavy

poles; where summer heat baked those same roads into hard miserable ruts, and

winter drifts obliterated them entirely. True, cows, pigs, goats, fowl wandered

where they would, and village streets were punctuated by reeking dunghills,

slops, and sewage (those lacking primitive privies attended to their needs in

the streets.) True, water could be deadly, and rivers

were fouled by night soil. And yes, such conditions are inconceivable in the

face of today’s fear of microbes, dirt, insects, birds, wildlife, odours, and

even natural vegetation, but do you think conditions were better in western and

southern Europe? In the new North American towns and cities? They weren’t.

That’s just what life was like back then.

Here’s what else it was like: there

was a silence we don’t know today, a calm that admitted voices from a

neighbour’s house, conversations on the street, taunts, laughter, sobs, the

sagging sounds of those reeling tipsily along alleyways. There was the barking

of dogs, the thud of horse’s hooves on dirt lanes, the jingle of decorative

horse bells, the rumble of wagon wheels, the singing of so many birds,[1] the

rustle of leafy trees. People hummed, sang, or whistled as they worked;

peddlers blew whistles and called out their wares in a singsong. The streets were alive with hawkers willing to exchange salt, tobacco, matches, needles, and ribbons for eggs, meal, bones, bristles, feathers, fowl, pelts, mushrooms, and berries. There

was the clang of blacksmiths and pot menders, the rasp of sawyers, the

hammering of carpenters and roofers, the terrified cries of animals being

slaughtered in roadways, yards, or on doorsteps. And every Sunday, red-booted

peasant girls and proud peasant lads would join arms, sing before the taverns

and inns, stamp their feet on the earthen road, while musicians (blind musicians,

Jewish klezmorim, pipers, or

fiddlers) played until dawn.

The aroma of sun-heated grain

floated on the air, mixed with the perfume of flowers and ripening fruit. There

was the hot reek of seeds being pressed for oil, and you could smell feathers,

animals, blood, rot, dust, black earth, grain, snow, wood smoke, filth, corn,

sun, rain, storms, and all the different seasons.

[1] According to the European Bird Census Council, the

farmland bird population has declined by 53 per cent in some areas, and by 70

per cent in others.

Excerpt 3

Outside, there’s a blizzard. Customs officials and train mechanics stamp their feet, trying to keep warm. Inside in this train carrying only a few passengers, life is pleasant, dreamy, and cosy. We aren’t advancing, merely jerking back and forth with a terrible grinding for, at the Romanian border, to overcome the differences in track gauge, wagons are lifted off one set of bogies and placed on another. This difference in gauge once slowed down panzer units dependent on ammunition and oil and helped prevent Hitler’s seizure of Moscow, but today, it’s a long, costly process. I’m one of the last travellers on the romantic-sounding Moscow-Sophia run. In two weeks, it will be cancelled, and no train will replace it.

After a final shudder of wheels and much thudding, we set off again, swaying through the soft white countryside, accompanied, since Czernowitz, by a narrow snow-covered Moldavian track. Forgotten, used only by farmers and shepherds today, a hundred and fifty years ago, despite its ruts, holes, and the frail horizontal poles bridging streams and quagmires, it might have been an important north-south way. Villages seem drowsy, empty. Swarms of starlings fill the air, fields maintain their long medieval swaths, and motionless shepherds are out on the frozen plain, timeless figures with crooks. Do they still follow the old custom of wintering where grasses pierce the snow? Apparently. Here and there are enclosures for their woolly creatures—odd-shaped reed-walled corrals. Close by are the modern shepherd’s huts: no longer made of stalks and thatch, these tiny one-room boxes have walls of corrugated metal, plastic sheeting, any old salvaged, knocked-together material. Iron pipe chimneys sprout from roofs. Bored sheepdogs, taking a break from rounding up their silly charges, happily chase our passing train.

I transfer at stations with the crenulated roofs of small castles or Moorish palaces, journey further with grizzled men sporting extravagant moustaches and old-fashioned headgear. They hold their shoulders back proudly. Just remove those synthetic jackets and we could be in another era. School children of all ages travel for a stop or two before setting out on foot through the snow, heading for some invisible homestead. One young man leaps agilely from the moving train, strides towards a hazy clump of houses and barns. I want to call out to him: ‘Take me with you. Let me, a nosy intrusive person, peek into your life for a short time.’

Silence without media interference is too much to bear for a few travellers. A scratchy radio is snapped on—happily, the music is traditional Romanian, jumpy, nervous, and catchy. A few moustached men hum, sing along, slap their thighs, and whistle shrilly at all the right places. I encourage them with nods and grins.

Excerpt 4

Falling snow obscures all. Surely no one will travel in such a blizzard. Even huge, snow-covered stray dogs curl desperately against the walls and doors of the central bus station. Take a look at the rusty mini-buses with threadbare tires in the station yard: those motorized tin cans will never risk ice-covered, potholed roads.

I’m wrong, of course. I’ve spent too much time in places where people are easily upset by weather. This is Ukraine; snow is normal. The unheated can I board joins other cans, cars, horse-drawn carts, and off we go, gliding along as if nothing unusual is going on. Even the driver is not in the least troubled by high drifts. As we slalom merrily, left, right, centre, left, half-spin, centre again, he chats amiably to the woman sitting just behind him. Further obscuring the view, a special metal attachment just above the windscreen allows for his impressive collection of good luck tchotchkele: toy animals—two bears, a bunny, a puppy—a bouncing crucifix, an icon, several splendid sprays of plastic flowers.

Svyniukhy (Svinich) is now called Privetnoye, and it’s some thirty kilometres away. On these bad roads, the trip there will easily take three or four hours, although I’m not certain about much of anything since I’ve also lost my modern road map and I can’t understand anyone anyway. Outside, white hills swell gently, and despite the snowstorm, a heavy mist makes time inconsequential. Perhaps it’s a curtain of sorts, one through which I must pass in search of the past. Yes, the countryside does resemble that of Michigan or Ontario—my grandmother said it would. Still, there’s something else out there, something quite unlike the New Country. Although Stalin ordered the collectivisation of smallholdings and the ploughing up of boundary brush, the traces of long strips, as narrow as the medieval past, are still stamped into the black earth by those long-gone serfs’ toil. Old mud roads are here too, just wide enough for carts and horses, heading toward villages hidden by hills and coppices. And, everywhere you look, those peasant women are there again, drab, bulky, lumbering homeward.

People climb into and out of the tin can at strange places, without dwellings, signs, or indications of any sort. Sometimes we pause in tiny villages with today’s usual jumble: ruined old houses with tin roofs; beautiful wooden terraces ruined by polyvinyl chloride siding; ugly new shops in cement; brick bungalows lacking style and charm but with effective heating; beautifully tended old houses of adobe with small double windows and, sometimes, a sculpted wooden entry. What I wouldn’t give to be invited into a few of those for a gawk.

The driver, exasperated that I speak no Ukrainian, lets me know it, turning, looking at me pointedly, sneering, making snide comments to smirking fellow passengers, all of them flat-faced, blue-eyed folk. Let him have his fun, I don’t mind in the least. I’m taking in the sight of the men and women trudging through the snow with straw baskets containing flapping chickens or heavy sacks. These tree-lined roads, carts and horses, unpaved mud streets, are visions from another time: yes, I have reached the other side of the curtain. What will I find in Svinich? Will I see the inn? Is there still a bench out in front? What about the river?

What’s so Exciting About

Writing Non-Fiction?

If

you think that writing non-fiction is dull, that it compares in no way to

fiction, you’re wrong. I write both, and although I do enjoy letting my

imagination create characters, conflicts, and landscapes, it is creative

non-fiction (also called literary nonfiction or narrative nonfiction) that is

closest to my heart. Why? Because creative non-fiction is a perfect blend of

memory, fact, and imagination.

What

exactly is creative non-fiction?

In

creative nonfiction, all information must be based on research, and nothing can

be invented. However, a writer can use personal experience to complete the

picture, and unlike pure journalism or academic work, creative non-fiction

reads like any good story, with conflict, a turning point, and vivid

description.

Twelve

years of research went into A Contrary Journey with Velvel Zbarzher, Bard, and

the result is a story set into an authentic nineteenth-century landscape, with

real people who are as flawed and doubting as the rest of us—after all, who can

relate to a perfect person?

Have

I convinced you? Here’s a short excerpt from, A Contrary Journey, and this

should do the trick:

I’m on the

wrong rusty mini-bus. The driver, a friendly roly-poly man, expert in dangerous

driving, hawking, and spitting, makes that clear. He and a few passengers

explain with gestures and shouts that this bus doesn’t go as far as Zbarazh—or

I think that’s what they’re saying. Who knows? Do I care? Despite the lack of

heating in this rotting vehicle, I’ve been lulled into contented passivity by

the sight of snowy fields and frozen lanes ambling on to nowhere in

particular…until the bus slithers to an uncontrolled halt and deposits me at an

empty crossroads. I’m to do the last four kilometres on foot? Fine with me. Can

anything be more exciting than walking into the village where Velvel was born,

where he grew up?

The flat

Ukrainian plain has given way to gentle Carpathian foothills and snow-dusted

conifers. Was this the very road Velvel took, going the other way, sneaking out

of town in 1844? The idea puts a delighted bounce into my step, and with my

cheap and trusty plastic camera, I snap pictures of the woods, misty hills, and

the frozen dirt track for horses and carts running alongside this paved

roadway. Until a sign announces I’ve arrived.

Comments

Post a Comment